Since a genius like Fanny Hensel spent her entire musical life in the shadows, it inspires me that living in the shadows musically, like I guess I do, is just fine and a worthy way to aspire to be a composer and musician.

I might as well mention my unhappiness with the music episode of the 1619 podcast here. When I first began listening to the presenter, Wesley Morris, narrate his ideas, I was discouraged that it was so anecdotal and a bit vapid. He describes spending some time a friend putting together a meal. They listened to a Pandora playlist the name of which I can’t make out. It consisted of Doobie Brothers, Seals and Croft. Morris was born in 1975 and seemed to relate to the music (as did I). Then he begins thinking about Black influence on the music he was listening to. This somehow leads him to a truncated discussion of the white invention of Minstrel Music but eventually sees Motown as a crowning achievement of Black music.

First I fact checked Morris a bit in my copy of Eileen Southern’s The Music of Black Americans (Third edition), and satisfying myself that he had indeed simplified the story tremendously (How else could you do so in a silly podcast?). Then I decided it would be only fair if I checked out his chapter in 1619 Project (the book). I learned that he can write good sentences which is no mean feat in my book. The music chapter begins much better then the podcast episode with him seeing a temporal connection between Birmingham Sunday (the senseless 1963 bombing of Street Baptist Church in Birmingham that killed young Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Denise McNair) and the Motown music on the charts at the time.

This was more coherent.

Later I learned that Morris is a staff writer for the NYT magazine and critic at large for the NYT. He is the only person to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism. And he has done so twice. It is confusing that he was asked to do the music section of this book and part of my frustration is the exclusive understanding of music as primarily popular culture and not art. I’m still reading his essay. I am expecting it to be better than the silly podcast he did.

And more importantly Adam Hochschild in his November 2021 review of the book version of the 1619 project helped me put the music comments in the larger perspective of what the book and the project accomplish. Which is quite a lot.

I am 100 per cent supportive and interested in learning the retelling and correcting of the history America’s slavery and subsequent white racism. And I have to grant that the 1619 Project had bigger fish to fry than my own love of music. Hochshild makes a very friendly, supportive, and clear-eyed critique and argues convincingly that the book and project ended up flawed but still very important. But he didn’t mention music.

So there’s that.

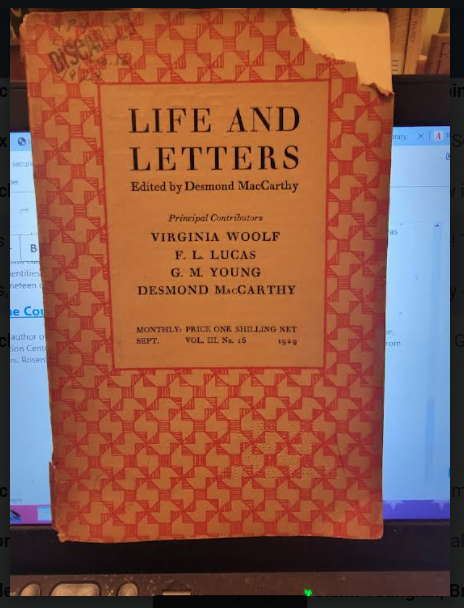

But I promised to mention how Virginia Woolf is helping me thinking about composing as well many other things. In my Thursday blog, I described how R. Larry Todd, the author of Fanny Hensel: the Other Mendelssohn, mentioned an essay by Woolf. His mention sent me up my stairs to see if the essay was in any of the books by Woolf I own. It wasn’t, but I did find a 1929 essay she published in Life and Letters a literary review of which I own a tattered copy.

The title of her essay is “Dr. Burney’s Evening Party.” I read it and was reminded how often Dr. Burney is cited in the biography of C. P. E. Bach I am reading. Burney was a fan of C.P.E and spent time with him. Woolf’s essay is not about C.P.E. but still it continued to expose me to how I can very modestly identify with people (women specifically) who are shunted to the side in our histories and stories. In this case, young Fanny Burney daughter of the doctor and a prolific diaries and essayist as was Burney himself. The difference is that he got all the limelight and recognition.

But this is not near as important as the inspiration I receive from the continual music of Woolf’s sentences. Here are the ones in this essay I quite like.

“But there was, one vaguely feels, something a little obtuse about Dr. Burney. The eager, kind, busy man, with his head full of music and his desk stuffed with notes, lacked discrimination.”

“To his [Burney’s] innocent mind, music was the universal specific. If there was going to be any difficulty music would solve it.

There were others but these are the only two I marked.

Susan Howe continues to inspire. Here’s a quote of her remarks in an interview regarding how she makes poetry. It rang true in my mind and reminded me of what it’s like to compose music.

“You open yourself up and let language enter, let it lead you somewhere. I never start with an intention for the subject of a poem. I sit quietly at my desk and let various things—memories, fragments, bits, pieces, scraps, sounds—let them all work into something.” Susan Howe, The Birth-Mark