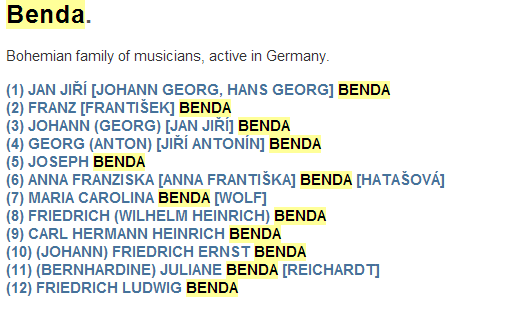

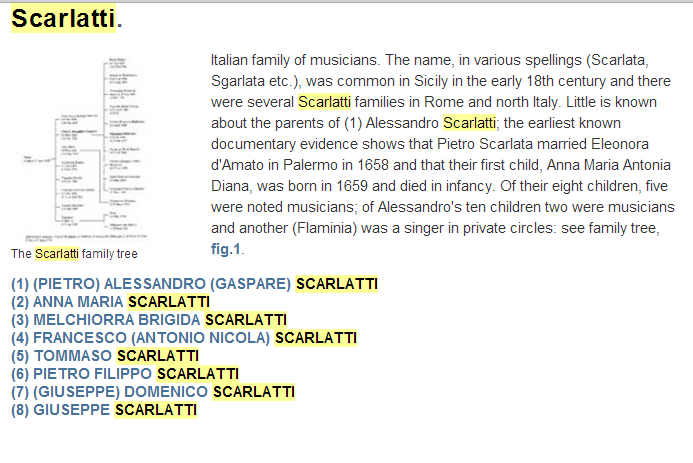

John Eliot Gardiner begins the fifth chapter in his book on Bach (Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven, 2013) outlining three musical dynasties besides the Thuringian Bach family, the Benda, Couperin and Scarlatti extended families.

(1) Jan Jiri, born 1686 (12) Friedrich Ludwig, died 1792.

(1) Louis, born 1626, Gervais-François, died 1826.

(1) Pietro Alessandro Gaspare, born 1660, Giuseppe died 1777.

(1) Pietro Alessandro Gaspare, born 1660, Giuseppe died 1777.

These musical families are roughly contemporary with Bach’s and are respectively from Germany, France and Italy. I have read about and performed music by many of the Bachs, Couperins, and Scarlattis. I’m sure I have played at least a few compositions of one of the Bendas, but was not aware of them as a musical dynasty.

It is odd that these families flourished at about the same time in history. It probably has something to do with the position of the musician in the societies at the time (a good way to keep the wolf from the door and often procure secure livelihoods for extended families). Also, there has to be something to be said for genes and mutual education and support in these circles.

Besides Bach, I am quite taken with three of these composers: Louis Couperin, François Couperin and Domenico Scarlatti. The music and stories of these men is something that has enriched my life.

I was amused by Gardiner’s blend of stiff non-Internet erudition with the slangy use of the term, “gig,” in a footnote about the last Couperin.

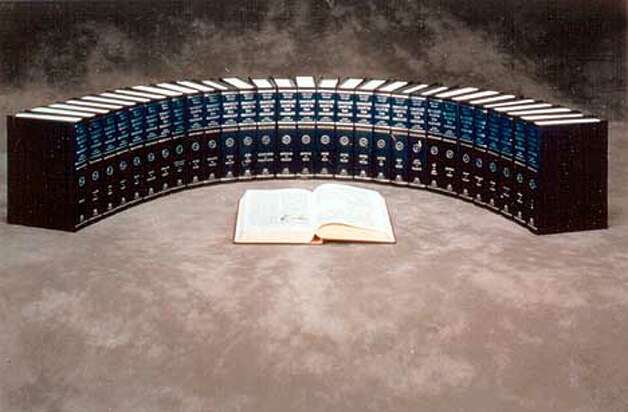

First he quotes from Groves (calling it the “New Groves”):

[I]n “one of the most bizarre scenes of the Republican aberration (6 November 1799), … [Gervaise-François Couperin] found himself playing dinner music on the greatest organ in Paris, at St Sulpice, while Napoleon and a nervous Directory, which was to be overthrown three days later by its guest of honour, consumed an immense banquet in the nave below, watched over by a statue of Victory (herself about to be overthrown), whose temple the church had become.”

Gardiner’s citation is oddly not from the online Groves.

![]()

Instead he tells us what volume (4) and page (873) he is quoting. Then he adds this comment:

“Somehow one cannot picture any of the Bachs, even at the nadir of their fortunes, undertaking an equivalent gig.”

So Gardiner is loose enough to use the term, “gig,” but old school enough to only cite the hard bound (thus immediately outdated) version of the New Groves.

I looked up this passage online in the New Groves. It was unaltered but Gardiner’s attribution to the author David Fuller who wrote the article was missing the full attribution of the additional author, Bruce Gustafson. Most probably Gustafson is responsible for additional newer material added to the online entry.

On the one hand, I am reading and enjoying Gardiner who is very educated and whose writing exposes a deeply learned mind capable of out thinking many scholarly approaches to his subject, but still seems to be a bit old school despite the avant-garde nature of his scholarhip.

On the other hand, I am also reading David Byrne’s How Music Works (2013) whose orientation is fascinating but much much narrower.

Byrne knows a lot about the world of commercial popular music. But this morning I came to the conclusion that Byrne sometimes writes with the arrogance of the uneducated young person. What they don’t know about doesn’t exist unless they are pleasantly surprised by stumbling across it somehow. God forbid they should research carefully or even look shit up.

I am now making a list of outright errors in the Byrne text. But I’m still enjoying the parts of his text that talk about his world, the world of commercial music, a world I don’t know that much about.