In my meeting with Jen yesterday, I showed her how different Sunday’s closing hymn, “Come, Labor On,” sounds in “A flat major” (the written key) and “G major” (transposed down a half step). She was surprised as I was when I discovered this.

It’s not only that “G major” is a bit more in tune. In fact, that’s not how I experience the difference. “A flat major” makes the hymn have a certain character that is difficult to describe. Maybe it’s a bit more aggressive.

In G major it is definitely smoother and feels more gentle.

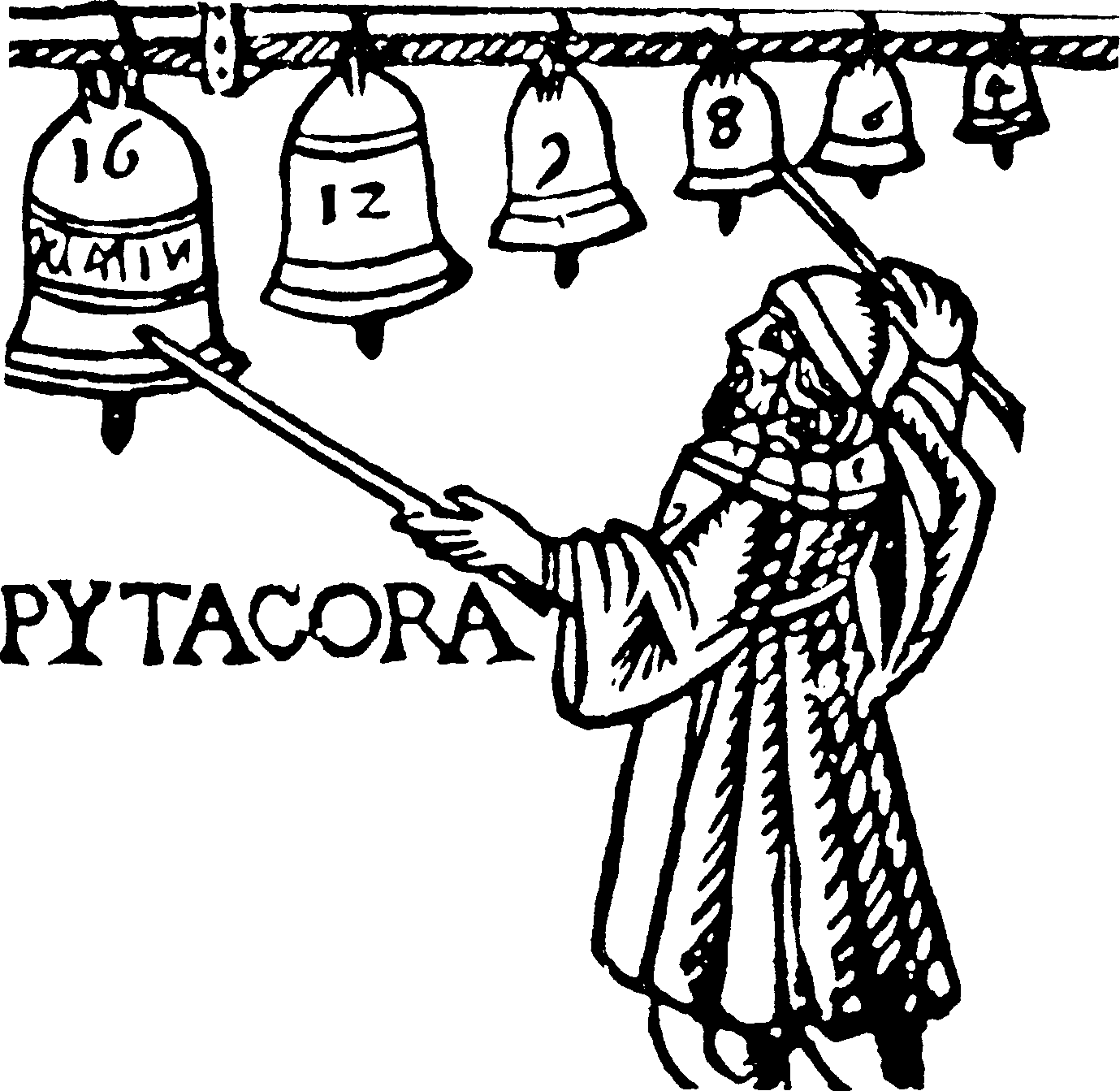

Jen is intrigued by the ideas of equal and unequal temperament. She has a scientific mind and background. She understood quickly that the difference is a numerical one that can be understood in terms of specific frequencies. She also recognized that Pythagoras developed some of these ideas six hundred years before the Common Era.

I have listened to musicians insist that different keys have different qualities all my life. But I never understood exactly what they were talking about. Being a keyboard player, I have usually made music that is essentially out of tune or as I was describing it to Jen yesterday “out of nature” or “not in nature.”

I’m surprised to find that I can tell the difference in character between theses two keys in this instance. I remember that Kellner, the man whose tuning Pasi uses with some modification, evolved his tuning after studying Bach’s organ music. Presumably, the changes in character are ones that Bach was well aware of. And Bach wrote in all keys but did not subscribe to equal temperament. Instead, the story is told that he used to drive his organ builder friends a bit crazy by transposing pieces into distant key to evoke the “wolf” or the little buzz one gets in one’s head when something is out of tune. Not sure where I read that, but it’s a good story.

I’m planning on playing the closing hymn Sunday in G major. But I don’t think it would hurt to do it in A flat major. The tune was written by T. Tertius Noble, a historically famous and important New York City organist. Since he died in 1953, it’s likely that as a keyboard player he spent his life immersed in the fudged system of equal temperament.

I’m blogging instead of doing Greek first as I usually do. I have been thinking a lot about participles, both in Greek and in English. Unsurprisingly, in Ancient Greek, participles are simpler than in English. In Greek they are adjectives formed from verbs (so far, anyway). But in English they can be adjectives or nouns formed from verbs. I usually think of participles in English as ending in “ing,” but this is not the only way they are formed.

Thus “going” is a participle in English, but so also is “gone.” An obvious adjectival use is “working woman,” but so is “burned toast.” An example of is “good breeding,” “breeding” being the participle.

Since in Greek participles are adjectives they have an 8 fold declension. This means that endings are specific if a noun is used as a subject in the sentence (nominative), the object of the subject (accusative), in possessive statements or phrases (genitive) and, most confusingly at all for me, indirect objects usually indicated in English with “to” or other prepositions (dative). In each case there is a singular form and a plural form. It’s not quite as bad as it sounds but it is a lot to remember.