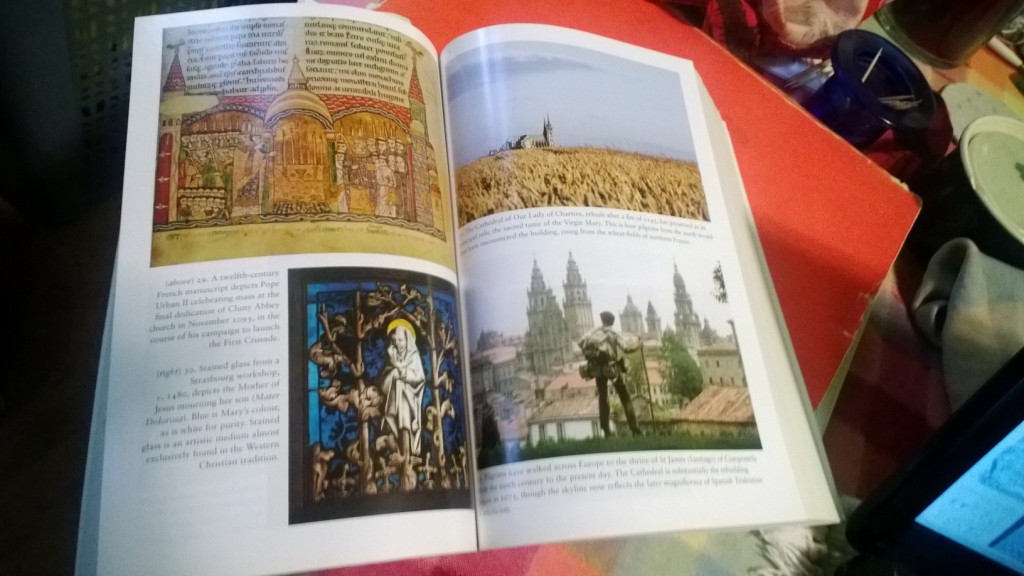

This morning, I returned to reading Silence: A Christian History by David MacCulloch. As I read it, I am also returning to his Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years for cross references. I have read the latter in its entirety once in an ebook. MacCulloch likes to send his readers back and forth in his books by citing page numbers. The Kindle book I read did not have the page numbers so I was unable to fully check things out while I read it. It also didn’t have the beautiful color plates.

This morning I was going back and forth between my hard copies of these two books. I resumed rereading the history of Cluny and its importance to the terrible time in Christian history when soldiers were sent to holy war, The Crusades.

This morning a terrible question occurred to me. What is the etymology of the word, “crusade”?

Yep. My suspicions were confirmed. Crusade the word is related to the word, cross. I find this both discouraging and ironic. I have been asking questions about how my church has used the cross symbol this past Lent and Holy Week.

I challenged my boss a bit when she preached a weird sermon about crosses (from which I stole today’s blog title). She developed the idea of “cross” as something one bears, an affliction in life.

My ears perked up when she said these crosses do not come from God.

I saw and still see this as a bit of a distortion of the liturgical understanding of cross as symbol and its place in what liturgists call the Paschal Mystery.

Upon questioning, Jen (my boss) revealed that her main concern at that time was the idea of evil, not crosses.

Even yesterday in my meeting with the clergy, there was some feeling that we shouldn’t call Good Friday, “Good.”

I basically don’t give much of a fuck about all this. I usually preface my comments and criticisms with a reminder that I am coming from a place of skepticism if not atheism.

But it bothers me when things don’t make sense to me.

So as you can imagine I am often wrestling with the difference between my understandings of stuff and what we are all bombarded with on a daily basis.

When the church talk turned to the idea of some churches that have changed the name of Good Friday to Holy Friday, I shuddered despite my atheism.

As we were chatting, I vaguely recalled some lines of poetry or something that addressed this. It was only this morning (with the help of Google) that I figured out what was rattling in my brain. Lines from the second of T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets:

The dripping blood our only drink,

The bloody flesh our only food:

In spite of which we like to think

That we are sound, substantial flesh and blood-

Again, in spite of that, we call this Friday good.

Jen relayed that during the children’s Stations of the Cross that she led on Good Friday, at the end of it, one of the kids asked what we call “Good Friday,” good.

We had a typical churchy discussion about this and her answer (which I can’t exactly remember right now). I’m seriously thinking of emailing Eliot’s happy little five lines with a link to the whole poem to my clergy staff. Probably a silly idea.

Which brings me back to the etymology of ‘crusade.”

What’s worse? A church service about the death of the christ or thousands of soldiers embarking on a holy war?

MacCulloch tells this little happy story

When Cluny Abbey fostered European pilgrimage to St. James in Compostela [SJ note: beginning around 1060], it was offering ordinary people the chance of access to holiness, like so much of the Gregorian Revolution. After all, the great attraction of pilgrimage was that it opened up the possibility of spiritual benefit to anyone who was capable of walking, hobbling, crawling or finding friends to carry them. But Cluny was also annexing to that thought another new and potent idea. St. James had become the symbol of the fight-back of Christians in Spain against Islamic power. It is still possible in Hispanic cultures as far away as Central or South Ameria to watch (as I have done in Mexico) Santiago’s image triumphantly processed on horseback, with a second image, the corpse of a Muslim, pitched over his saddle. p. 381 Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years.

Maybe I should send that happy little quote to my clergy as well.