It seems that in establishing brand names the complexity has proliferated to a comical degree. When I make up my grocery list, if I want to be sure to purchase a certain product, I can’t say simply ginger salad dressing. I have to begin with the “brand.” Then add subgroupings that the manufacturer has come up with like “honey mustard” and “yogurt.” Thus several designations are necessary to remind me to get the right dressing.

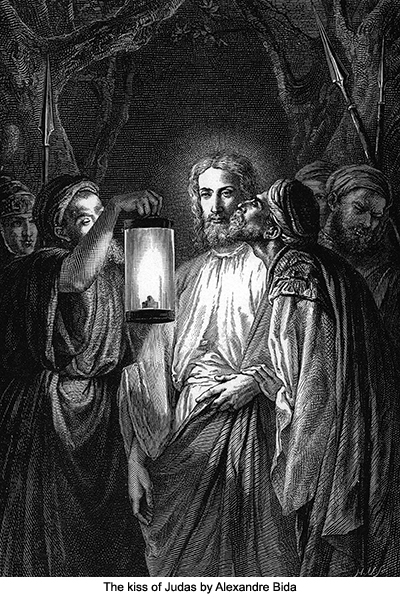

I was thinking about how this ends up devaluing language in a useless way, when it occurred to me to consider the word, “brand.” “Brand” is obviously both a verb and a noun. According to the OED (unless otherwise specified, all my info in this post comes the online Oxford English Dictionary), the first usage of “brand” in English occurred c950 in a translation of John 18:3. It means a “torch.” In the passage where the word is documented as being used, Judas is carrying a “brondum” (Old English) to guide himself and the soldiers he has tipped off as they make their way to arrest Jesus in the garden where he is praying.

The etymology is complex. But basically burn, brand and boil descend from Greek words for warm (thermos) and for spring as in a boiling up of water in a spring (phrear).

I got this info from a combined use of the free online American Heritage Dictionary (which next to the paid online OED is useless) and also consulting my hard bound copy of the same.

I ran across the other useage of the word, “brand,” in The New American Jim Crow.

Four decades ago, employers were free to discriminate explicitly on the basis of race; today employers feel free to discriminate against those who bear the prison label—i.e., those labeled criminals by the state. The result is a system of stratification based on the ‘official certification of individual character and competence’—a form of branding by the government. The New American Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander, loc 3088, p 202

So the dehumanizing practice of burning an identifying mark on a human relates to the devaluing of language in a simple marketing tool. Wow. Some things to think about.

Good nonfiction authors often muse on and define limits for words they are using. Zuckerman in Rewire ponders the origin of the word, ‘serendipity.” Since Zuckerman is thinking about how our connections both to information and to each other are working these days, it’s not hard to see why he would be thinking about this word. He even goes further and advocates “designing for serendipity.” This intrigues me and I look forward to his further discussion in the book as I read it.

The OED confirms Zuckerman’s story about this word. It was coined by Horace Walpole in 1754

He did so in a letter he wrote referring to the fairy tale, “The Three Princes of Serendip” ” the heroes of which ‘were always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things they were not in quest of’.”

If you’re like me, you think if serendipity as a “happy accident.” Zuckerman tellingly points out that it has lost some its original resonance as also containing “sagacity.”

This sage or

this one?

Anyone who has done research in a physical library knows about “serendipity.” Searching the stacks for one book often leads to other books in the same vein which can be helpful.

I was recently commenting to the local college library that accessing their journals solely through the catalog did not enable me to browse the latest titles the way I used to be able to. Lost serendipity? Who knows.