There is of course a pleasure in holding a published book in your hands when you read that cannot be duplicated (so far) by an ebook reader. I find this particular pleasure varies immensely from one book to another. A book that is beautifully made and designed attracts me physically one way. Another book that is old and worn and falling apart attracts me in a different way. A book that was owned by someone I love who is now dead or far away is another way.

Having said all that, I am convinced that holding a book like Diarmaid MacCulloch’s Silence: A Christian History in my hands conveys information and thought in a much different way than an ebook does.

First of all there is the physicality thing again. My copy came in the mail recently and I find the paper of jacket cover pleasurable to touch and the weight of the book in my hand satisfying.

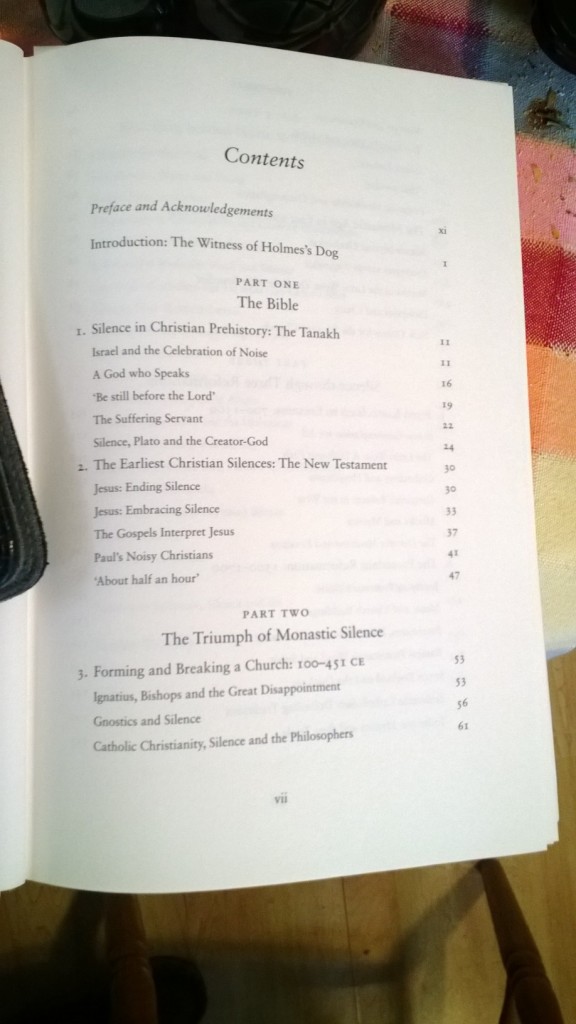

But more importantly, the layout of the Table of Contents is very helpful in perceiving just how MacCulloch is planning on talking about his subject.

Then I take a quick look at the back of the book and notice the many footnotes, the further reading section.

As I begin to read, the footnotes interest me greatly. MacCulloch writes excellent footnotes and loads them up with opinions and ideas as well as references to sources.

I have listened to this book as an audio book and as usual it only basically whets my appetite for reading the book more carefully.

MacCulloch begins by referring to two mystery stories with dogs in them that either bark or don’t bark (heading towards thinking about silence in larger ways such as absence).

In “Silver Blaze” by Arthur Conan Doyle, a dog doesn’t bark and it is significant to how Sherlock Holmes solves the case. In “The Oracle of the Dog” by G. K. Chesterton, a dog’s bark is misunderstood as oracular in the sense that somehow the dog knew a murder was taking place.

As you can see, I have found these two stories online. I used the “Send to Kindle” app to send them both to my Kindle so that I can savor them and MacCulloch’s point.

I also immediately went to this section in MacCulloch to read on the page:

“All through my historical career, I was keenly aware of the importance of silence in human affairs, for a good biographical reason: from an early age, I was conscious of being gay, and that proved to be a great blessing for a young historian… this life experience has left me alert to the ambiguities and the multiple meanings of texts, and to the ambiguities and multiple means in the behavior of people around me. I have become attuned to listening to silence and to finding within it the keys to understanding many situations, far beyond anything to do with sexuality.”

And this section:

“As a gay child and teenager, I also effortlessly developed the historians’s other essential quality, a sense of distance: an observer status in the rituals constructed for a heterosexual society in a world which in reality was not quite like that.”

In the week before Christmas, attempted to make these two points to my boss (who is gay) in one of our conferences. She said to me, “I needed that.” Me too, actually.

Referring to what happens when silence ends about sexuality, MacCulloch charmingly writes:

“Inflexible pattern-makers get very angry when their patterns are under threat, or when others offer new patterns, or when it is pointed out that there are parts of the pattern missing; that is why so much conservative religion in the modern world seems so deeply and perpetually cross.”

I am definitely not thinking of the crazies who committed the recent tragic and atrocious shootings in Paris, instead using MacCulloch’s ideas to think about American conservative religious type helps me. They are definitely “cross” at times.

So savoring ideas for me works a bit better book in hand. But I’m not giving up my little screens.