The last few mornings I have been reading poems by Wendell Berry from his volume, This Day: Collected and New Sabbaths. The book was a Christmas gift from my brother, Mark (thank you, Mark!). The day I opened the gift I accidentally tore the cover. I was mortified since it is such a beautiful book and immediately hid it from the rest of the people in the room. Despite this, I picked it up this week and started reading.

I have read all of the poems from 2012, the last section in the book. I am curious how sane people like Berry view things from the vantage point of being alive today.

I also read the “Preface” and “Introduction.” I was amused to see Berry commenting on the word, “spirit,” which reminded me of yesterday’s blog on Merton’s sentence on art. I am still reading Merton but finding him less entrancing, more dated. Berry (and another writer whom I will mention in minute) seems a bit of an antidote.

Berry says this about “spirit.”

“In the earlier poems [of the collection] I used the words “spirit” and “wild” conventionally and complacently. Later I became unhappy with both. I resolved first to avoid “spirit.” This was not because I think the word itself is without meaning, but because I could no longer tolerate the dualism, often construed in sermons and such as a contest, of spirit and matter. I saw that once this division was made, spirit invariably triumphed to the detriment, to the actual and often irreparable damage, of matter and the material world.”

“Dispensing with the word “spirit” clears the way to imagine a live continuity, in fact and value, between what we call “spiritual” and we call “material.”

Good point. Not sure how this connects to my little story about all music being “spiritual.” To a musician like myself who is bound to music as an action Berry’s duality might not obtain with quite the same force it does to him. Underlying his poems and stories is always his concern with our lack of stewardship of the “material world.”

Earlier in the preface, Berry indicates that these “poems were written in silence, in solitude, mainly out of doors. A reader will like them best, I think who reads them in similar circumstances—at least in a quiet room.” He goes on, “They would be most favorably heard if read aloud into a kind of quietness that is not afforded by any public place.”

This reminded me of my practice of reading poetry aloud. I haven’t been reading much poetry lately. So this morning I read Berry aloud in to my “quiet room” and early morning solitude.”

At the end of the introduction, Berry comments that his “thoughts have returned again and again to the practice devotion to Nature in the poetry of Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare, Milton, and Pope.”

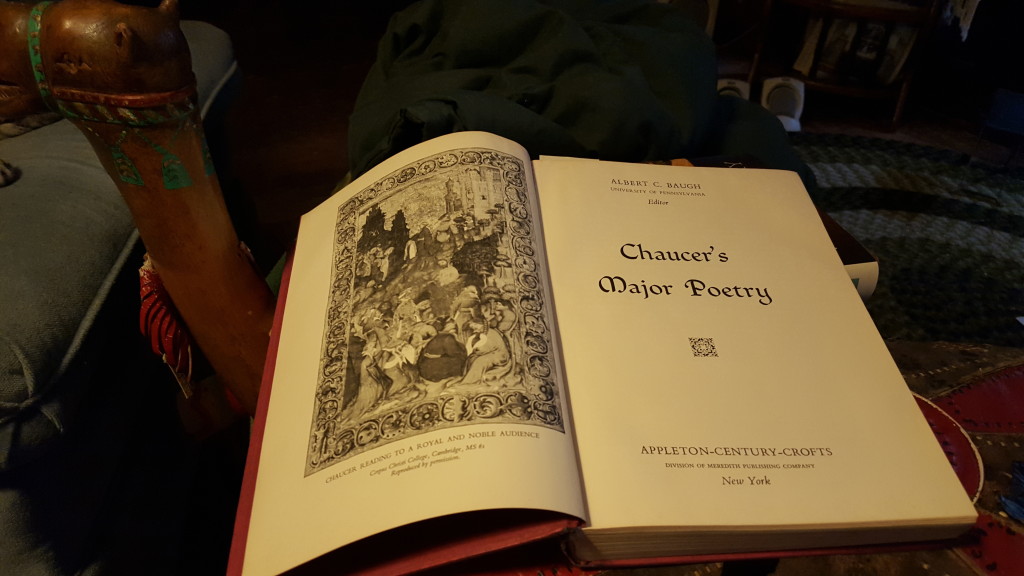

All of these poets are ones I admire. I had the impulse to pull out Chaucer. This morning I read several pages aloud of his poem “The Book of Duchess.” This is a larger poem and not from the Canterbury tales.

The mention of Chaucer always seems to evoke a dusty, stiff academic atmosphere. But then reading him one remembers the strong charming personality of the poet that seems to shine through all his work.

For sorwful ymagynacioun

Ys alway hooly in my mynde

from The Book of Duchess by Chaucer, 14-15

This edition has copious helpful information in it about the poetry. A footnote informs the reader about Chaucer use of the word ymagynacioun: “Jehan le Bel, a contemporary of Chaucer… explains imagination as the faculty which retains what is perceived by the senses; here equivalent to memories, thoughts.” from Chaucer’s Major Poetry, Albert C. Baugh, editor