The dance department chair, Linda Graham, and Julie Powell, one of the instructors I work with, cornered me yesterday and asked me if I would be willing to add two more days of classes next term. I told them no. It’s flattering to be asked and I do enjoy the work but I need to pace myself and balance my activities with my energy.

I did manage to squeeze in my requisite two hours rehearsal of Sunday’s postlude. I asked Jen, my boss, if she thought it was goofy to play a seven minute postlude. I have colleagues who have quit playing postludes due to people’s inattention.

I do not mind finishing a piece alone but I want to continue to examine the appropriateness of my work as a professional church musician.

Jen was enthusiastic in her support for this. When I mentioned that the St. Anne Fugue (the piece in question) was not actually based on the hymn tune it resembles she also agreed I should put a little note in the bulletin about this because it’s kind of interesting.

So I did that.

Reading about the “preluding” practice of performers from Bach to Beethoven has provided me with a number of insights about music I have been looking at most of my adult life.

Once some music puzzles have been set into the context of the expectation that performers would add music to concerts, they make more sense.

An example (which Kenneth Hamilton gives) is Mendelssohn’s “Song without Words” op. 30, no. 3.

The strumming chords at the beginning (which seem unrelated to anything that follows) is exactly what a musician might do as a set-up prelude for a piece to follow.

I had another insight provided by factoring in this process. Preluding is exactly what one does when one introduces a ballet exercise or a hymn to be sung by a congregation.

In the latter case, I often improvise an introduction to a hymn and do not slavishly play the last four measures to introduce it.

When serving as a ballet class pianist for the International Cecchetti camp that is held here in Holland I ran into one teacher who was dissatisfied with my introductions (called “preparations” by the ballet people).

Usually I try to be very clear and end my preparation on an unresolved feeling chord. One teacher balked at this. She said my preparations felt incomplete to her.

I of course adapted and quit doing that for her classes and did a prep with a resolved ending. I concluded that this was probably the practice of the teacher’s regular pianist.

Somewhere in Hamilton he mentions that preludes before a piece normally did not resolve but left a sense of wanting to go on to the piece itself.

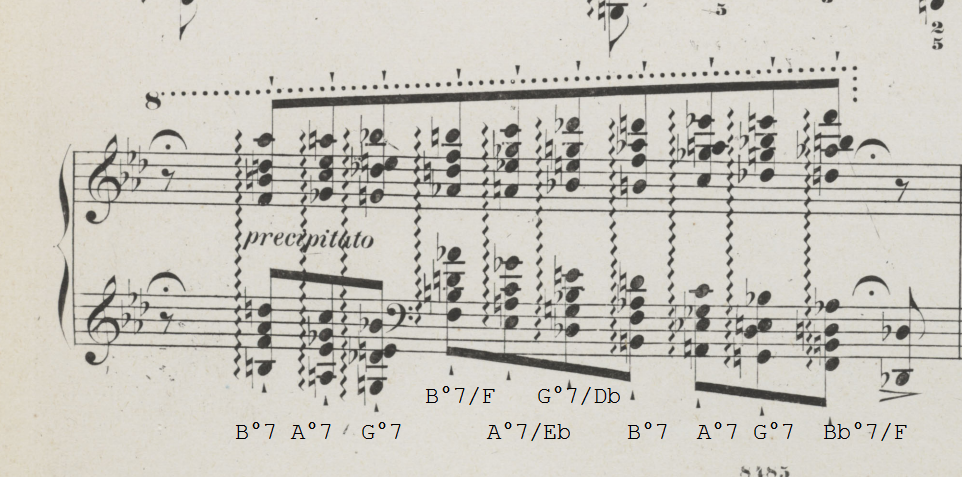

Apparently when moving from one piece to another this was done with a series of unresolved chords (which musician call diminished sevenths) which are very easy to use to change from one key another. This change was often the goal of the improvised interlude.

This lack of resolution in an improvised prelude or interlude introducing an upcoming piece helps me feel that my choice of doing the same thing in a preparation for a ballet combination is justified.

Silicon Valley CEOs Get A Warm Washington Welcome To Politics

Our own Fred Upton.

Escape from Microsoft Word by Edward Mendelson | NYRblog | The New York Rev

How Word is a work of genius, but useless. Hi tech, lo efficiency.

Political Polarization & Media Habits | Pew Research Center

Dang liberals are more ideological than conservatives …. interesting findings.